The Bizarre History of Tetris – The Russian Game That Took Over the World

Time passes, but we still love those colorful falling blocks.

Historically, it’s one of the most ported video games ever. Many others, like Columns or Collapse, have tried to imitate it but never reached its level. Tetris basically created its own genre within the arcade scene.

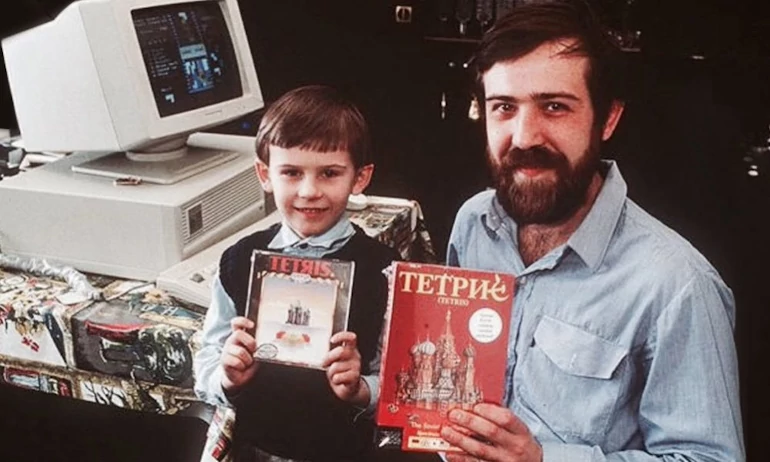

In 1985, a Russian programmer named Alexey Pajitnov invented it while working at the Moscow Academy of Sciences. After spending hours surrounded by wire frames, pyramids, and other interestingly shaped objects to test new computers, inspiration struck. Starting from a pentomino puzzle, he developed (legend says in just one afternoon) a game with seven shapes made of square blocks on an Elektronika 60 computer. Thus, Tetris was born—derived from the Greek word tetra, meaning "four"—and it became one of the most important video games of all time. Possibly one of the few where you can never truly "win."

This original version was very different from what we know today. It was text-only, working with just letters and numbers. The screen was black and white, with no color or sound, displaying asterisks while the blocks were represented by brackets. But the real challenge wasn’t the programming itself (which today is easy to replicate) but the original idea. That’s why, along with the Towers of Hanoi, it’s a favorite among beginner game programmers.

But we must emphasize—the idea was the most important part: the game’s mechanics. Second came its rules, simple enough to be understandable while still presenting a challenge. And even though 3D design is trendy now, our brains aren’t really wired to think in three dimensions for a game like Tetris due to intuitive spatial reasoning.

Just remember what happened with two puzzle games from the '90s: Blockout (fully 3D) and Welltris (2D). Welltris was one of the top ten best-selling games at the time, but Blockout wasn’t. So, if you want to create a 3D puzzle, you have to be careful. Converting a game to 3D isn’t a technical problem for programmers—the issue is whether people can actually play it.

The game started gaining popularity when a 16-year-old working at the Academy ported it to IBM PC. From there, it spread freely to Hungary, where it was programmed for Apple II and Commodore 64. These versions caught the attention of Robert Stein, who sold the concept to the British company Mirrorsoft and its American subsidiary, Spectrum Holobyte.

Soon, Atari and Nintendo fought over its license, with Mario’s company winning and releasing it alongside their new handheld console, the Game Boy. Atari countered with Klax, a puzzle game similar to Columns. For many years, the Game Boy version was the best—the blocks fell smoothly, and you could see them as they descended. Despite the game’s massive sales, Alexey didn’t start earning royalties until 1996. Before that, the money went to the Academy and the Soviet Ministry of Trade. To fix this, he moved to the U.S. and, with Henk Rogers, founded The Tetris Company (now called Blue Planet Software) to develop and patent all Tetris-related products.

Today, Tetris has sold over 50 million copies, and its creator now designs puzzles for Microsoft. The latest version includes six game modes, each aimed at a different audience.

This article would feel incomplete without explaining the game’s mechanics. Even if it seems obvious, there might still be someone who doesn’t know how it works. Playing Tetris is simple, though mastering it is hard. Despite graphical updates in newer versions, the core gameplay remains the same as Alexey’s original: blocks (initially seven different shapes, though later versions added more) fall from the top of the screen in different positions.

The player can’t stop them from falling but can rotate them (0°, 90°, 180°, or 270°) and choose where they land. When a horizontal line is completed, it disappears, and all blocks above it drop down, freeing up space and making it easier to place new pieces. The falling speed increases steadily. The famous Game Over happens when the blocks pile up beyond the play area. But the best part? If you’re good, there’s no real ending—unlike finishing Quake. A game can last as long as you’re alive.

Now, here’s a fun fact about Tetris: Since the block distribution is random, you might get a long sequence of Z-shaped pieces. This forces you to leave a gap in the right corner with no way to fill it. If a bunch of S-shaped pieces follow, the blocks pile up, and you lose.

Assuming the block generator were theoretically perfect (in reality, it’s a linear congruential generator), a player could survive about 150 S or Z pieces in a row. But the odds of getting 150 straight S or Z pieces are about the same as the number of atoms in the known universe. Crazy, right?

And now, the million-dollar question: Why did Tetris become so popular? From what we’ve gathered, there are two theories:

- It taps into the human need for order and harmony.

- All our achievements—the blocks we neatly arrange—disappear as soon as they line up, leaving only our mistakes in front of us, making us want to fix them endlessly.

But hey, just theories.

Leave a Reply